So, we all know Star Wars now as a galaxy far, far away filled with lightsabers, epic battles, and the world’s most recognizable theme music (thanks, John Williams). But before it became the sci-fi juggernaut that reshaped the entire film industry, the movie existed in a much rougher form—a version that had George Lucas’ filmmaker friends worried sick for him. Yep, the Star Wars rough cuts were a thing of legend (and, sometimes, confusion).

Today, we’re taking a look at what went down with these early versions, and how they evolved into the cinematic masterpiece we love. Grab your blasters (or a strong cup of coffee), and let’s dive in.

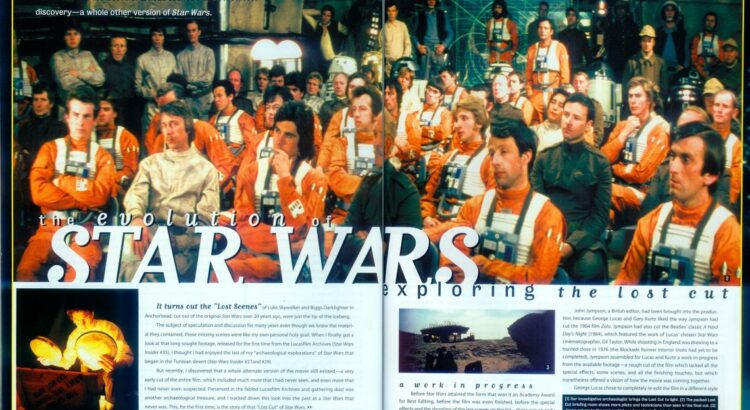

The Legendary “Lost Cut” – A Different Star Wars Universe

Let’s start with the most famous early version of A New Hope—the “Lost Cut.” After wrapping up filming, George Lucas handed over the raw footage to British editor John Jympson. What came out of this collaboration was an entirely different movie. And not “different” in the “Hey, look at all these fun bloopers” sense—this was a version with a radically different feel.

What Was the Lost Cut Like?

According to those who’ve seen it (a lucky few, as this version isn’t publicly available), the “Lost Cut” was more like a slow-paced documentary. About 30-40% of the footage differed from what we see in the final film. Key scenes, like Luke Skywalker’s time hanging out with his buddies at Anchorhead, were much longer. Imagine a long, leisurely hangout on Tatooine where the biggest plot development was some desert boredom—essentially American Graffiti in space.

This cut lacked the energetic pace that would later become one of Star Wars’ most defining features. There were no explosions, no high-speed chases, and no John Williams score (we’ll get to that!). Instead, Jympson had pieced together extended takes of scenes that were later trimmed down for the final release.

Quick Lost Cut Facts

Let’s hit some of the highlights of this mysterious version:

- The Lost Cut was edited by John Jympson, stored on 35mm film across 13 reels.

- 30-40% different footage: extended Tatooine scenes, more of Luke’s buddies at Anchorhead, and longer Death Star sequences.

- The cut lacked special effects, with temporary live-action backgrounds standing in for the futuristic ones we’re familiar with today.

- Early drafts featured human Jabba the Hutt before the alien version was conceived.

When Warplanes Stood in for X-Wings

Here’s where things get interesting. Since the visual effects weren’t ready (ILM was still figuring out how to make spaceships blow up), placeholder footage was used. And by “placeholder,” we mean stock footage of World War II dogfights. Imagine watching Star Wars with old black-and-white Japanese bomber planes instead of X-wings. Yep, that’s what Lucas’ friends had to deal with.

Why George Lucas Hated It

George Lucas, like a director after an all-nighter in the editing room, was not happy. He felt that the pacing dragged, the narrative lacked excitement, and the selection of takes didn’t fit his vision. Essentially, the film felt flat—more like a slow melodrama than a space epic.

To fix the problem, Lucas brought in new editors, including his wife at the time, Marcia Lucas, along with Paul Hirsch and Richard Chew. They trimmed the film down, removed extraneous scenes (goodbye, Anchorhead!), and injected a much-needed sense of urgency.

Friends to the Rescue? Spielberg, Coppola, and the Early Screenings

Before the final cut was ready, Lucas showed the rough cut to some of his closest filmmaking buddies, including Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, and Brian De Palma. And, uh, let’s just say the reactions were…mixed.

Steven Spielberg: The Optimist

Steven Spielberg, always the supportive friend, saw the potential in Star Wars even though it was essentially a skeleton of a movie. According to Spielberg, the effects were barely there, and most of the film felt incomplete, yet he could see the direction Lucas was heading. Spielberg later admitted that even in this early stage, he believed Star Wars would outgross his own movie, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (and boy, was he right!)

Brian De Palma: The Critic

Then there was Brian De Palma, who didn’t hold back. He famously ripped into the rough cut, loudly expressing confusion and frustration. His exact words? “I DON’T UNDERSTAND YOUR STORY! THERE’S NO CONTEXT! WHAT IS THIS SPACE STUFF? WHO CARES?” De Palma didn’t mince words, and Lucas reportedly took some of the feedback to heart.

But let’s give De Palma credit where it’s due. He’s the guy who helped rewrite the now-iconic opening crawl. Lucas’ original crawl was apparently a confusing mess of “gobbledygook,” so De Palma, along with screenwriter Jay Cocks, reworked it into something that actually made sense. So next time you’re reading those yellow words scrolling into the starry abyss, you’ve got De Palma to thank.

Francis Ford Coppola: The Worried Friend

Coppola, meanwhile, was concerned. Really concerned. He thought the movie was in trouble, especially without the music and effects to help sell the illusion. In fact, he was so worried for Lucas that he reportedly offered to help finance the movie himself if the studios didn’t want it. Now that’s a good friend!

The Game-Changer: Enter John Williams and ILM

Let’s be real—without the score, Star Wars would be a totally different experience. When Lucas showed that early cut to his friends, John Williams’ iconic music was nowhere to be found. Instead, the film was accompanied by temporary tracks from classical music composers like Holst.

Once Williams came on board, the score added the emotional depth and grandiosity the film needed. Combined with the revolutionary visual effects from ILM, the final product became the space opera we all know and love today.

A Final Word on the Rough Cut

The rough cut of Star Wars: A New Hope serves as a fascinating glimpse into the creative process—proof that even legendary films start out as far-from-perfect drafts. It was a rough ride, complete with stock footage, missing effects, and confusing storylines, but through a combination of skilled editing, relentless post-production, and the magic of John Williams’ score, Lucas and his team transformed it into a cultural phenomenon.

So, next time you’re rewatching A New Hope, remember that before all the glitz, glamor, and Ewok celebrations, it was a far humbler project—just a guy with a vision, a few confused friends, and some old warplane footage.

Related Reading:

- “How George Lucas’ Early Star Wars Vision Was Saved by Friends”(ComicBook)

- “The Evolution of Star Wars: From Rough Cut to Cinematic Masterpiece”(Lost Media Wiki)(Wikipedia)

For more cool facts, check out T-bone’s in-depth dive into the Lost Cut.